A Story About A Story

Meet my friend Earthell Latta. When she first approached me at the Davidson-Cornelius Day Care seventeen years ago and asked me to write her story, neither one of us had any idea where that journey would take us.

In 1971, when she and her sister were young, they were taken, perhaps kidnapped, by a traveling evangelist, and were on the road, wandering through Georgia and Florida for months before a private investigator finally found them.

As a writer with a few local histories under my belt (a centennial history for the Town of Cornelius and a bi-centennial history for the First Presbyterian Church), I naively figured telling Earthell’s story would unfold in a similar fashion, i.e., I’d conduct some interviews, do some research, and make some site visits—et voila! a book.

However, talking to her extended family, visiting her old house in Druid Hills, and reading microfiche versions of the Charlotte Post resulted in nothing resembling a nice, organized timeline from which a book would emerge.

All I had was a specific start and end date with nothing but whispers and fragments in between. Family members’ memories didn’t agree. There were no traces to be found of many people connected to the story. The FBI wouldn’t release any files for those involved without death certificates.

I could have admitted defeat and told Earthell that the project was beyond me. But you know, EGO. I didn’t let go and hung on, using various tactics to flesh out the story, including one awful draft with a parallel plot line where two white girls are on their own trip to Florida at the same time. (I’m red as a bottle of Heinz typing this.)

Four or five years ago, Earthell and I met at a restaurant to review the first sixty pages. Any writer can testify to the fear we feel when showing someone early drafts of our works in progress. Please like it, we silently plead; our entire self-worth is tied up in those typed pages.

What I failed to take into account was the fear the subject of those pages must feel when encountering their life laid bare for all to see.

Those sixty pages were cobbled together scenes based on early interviews and basic research; they lacked critical details; they lacked nuance. Desperate for more information, I peppered her with questions—what did she remember about her house? her kitchen? her clothes? Earthell, offended, snapped, “My house had everything normal! Beds, chairs, sofas, toiletries.”

Though there was only a restaurant table’s width between us that day, it felt like Death Valley.

Up until then, we hadn’t given much thought to our differences; after that we couldn’t ignore them.

Instead of giving up, we tentatively walked toward each other across that vast desert of unknowing. We learned how to listen to each other; how to hear not only what the other was saying, but what we meant. We established trust.

I explained why I was curious; there was no judgment on my part, merely a need for details so that I could better tell her story. She relaxed a bit, recalling the salt and pepper shakers on the kitchen table and then the table itself, how proud her mother was of its shiny chrome trim. This led me to wondering where the dinette set might have been purchased. Back at the library, in old telephone books and city directories, I found Lee Thrasher and his “acres of furniture all under one roof”—better scenes began to form.

Much of her story centers on food and the lack of it during their journey. Earthell stressed that she was never hungry at her mom’s house, but she had loved the individually wrapped slices of cheese that her aunt had. She shared how much she’d hated the hard-boiled eggs her mom used to put in her lunch and how she’d throw them out the car window.

I devoured these delicious details like a finalist on Alone.

As Earthell says, the book is really a story about a story. Because there is no way of uncovering the truth about everything that transpired, we agreed that her story would be better told in a novel—as fiction. So it is not exactly what happened to her and her sister, it is a story about what happened to them.

Writing the book also became a story about us. While we hung on to the goal of making it work, we bridged the enormous gap that once separated us.

A few weeks ago, Earthell and I returned to her old neighborhood, an area of Charlotte now considered “up and coming.” The house where she once stayed on Norris Avenue has been bulldozed; there is an “an open-air artistic hub” a few blocks away. The neighborhood has changed a lot.

We have, too.

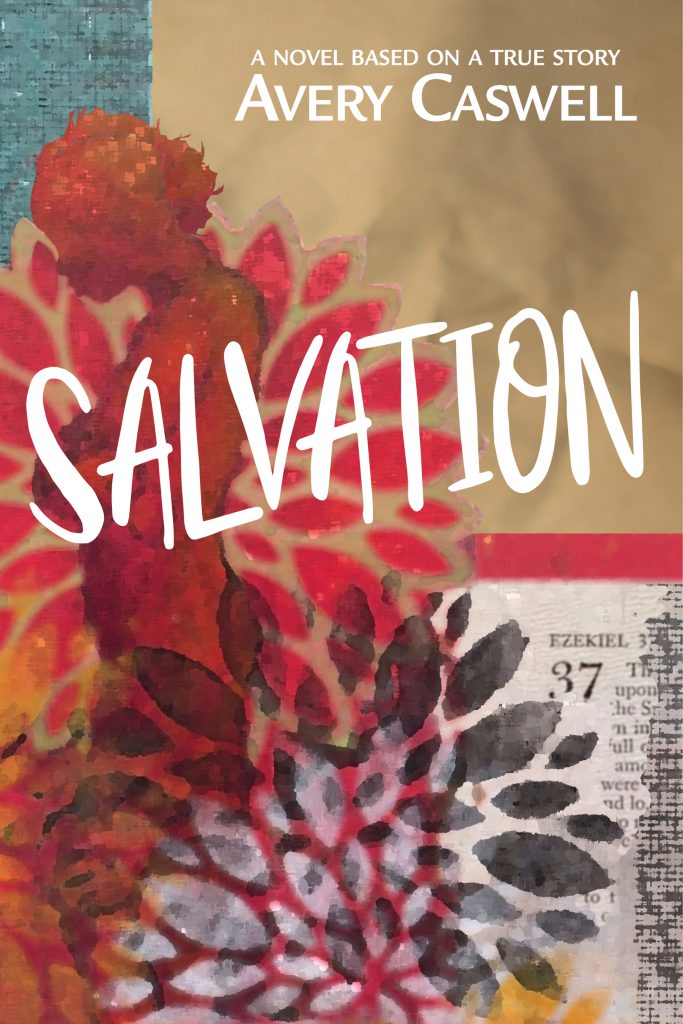

Salvation will be released September 15, 2021. It would mean so much to Earthell and me if you’d share our story and order a copy today. Available through Amazon and anywhere you like to buy books.