Loose Ends

3/11/17. Two days ago, it was over 70º and this morning, there was more than an inch of snow on the ground. Had T. S. Eliot lived in the Carolinas, “The Waste Land” might have read,

March is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

A lot of us today are thinking, “Climate change!” but to be honest this is not the first March that has played havoc with the weather. It often does the unexpected. Some call the month fickle, others indecisive. Maybe it’s the Piscean nature of the calendar, those two fish, swimming in opposite directions, one looking back at winter, the other forward to spring. Maybe it’s just pure greed, wanting it all, all at once: snow and snowdrops, iris and ice, cherry blossoms and chilly air.

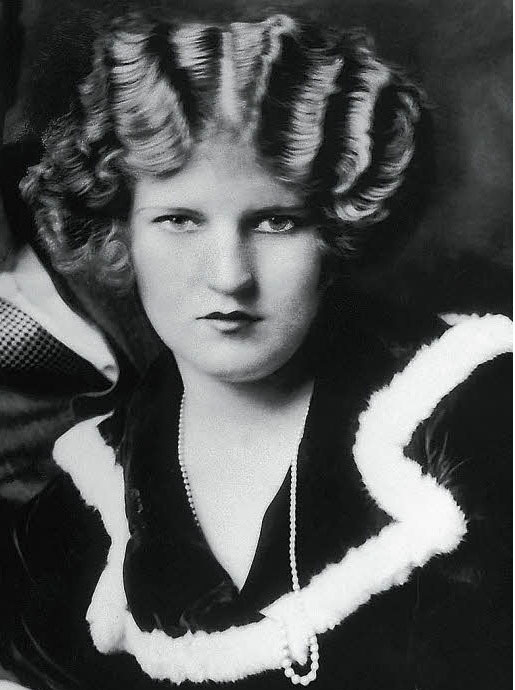

T.S. Elliott has another raison d’être in this second post of my “What If” year. Elliott had a cameo in Midnight in Paris, Woody Allen’s movie about pining for the so-called Lost Generation, the 1920s literati. So did Zelda Fitzgerald, the only person I could find who made a legitimate “loose ends” quote. (If you haven’t seen this movie, and especially if you love Paris, pull it up on Netflix.)

I seriously thought I’d cruise right into a post about “loose ends.” I planned to search “loose ends” on Brainy Quotes, choose a quote, and write away. (I secretly expected to discover that the phrase originated with Shakespeare.)

Well, no such luck. All kinds of quotes on being loose, getting loose, and playing loose, but only this one from Zelda on actual loose ends:

It is the loose ends with which men hang themselves.

—Zelda Fitzgerald

What did the unstable, effervescent, irreverent Zelda mean?

The dangling threads of unfinished, or partially finished, projects trip us up. The undone can become our undoing. Better to finish completely that which we begin. Not finishing might spell disaster, or worse, death. Death to the dream, the soul, perhaps even the self.

I’m working hard to complete something that I began more than a decade ago, a project that I said yes to even when I knew at the time I was not skilled enough to do it justice.

Since I have been given the gift of time with my writer-in-residence appointment at Lenoir-Rhyne, I am focused on finishing the story of two young girls who were kidnapped (or not) by a traveling evangelist who visited Charlotte, NC in 1971.

Years ago, after one of the kidnap victims asked me to write her story, I interviewed her, her sister, their mother, their aunt, and cousins. I holed up in the Carolinas Room at the library and read articles in the Observer and the Post, newspapers published in 1971. I dug deep into Charlotte’s history. That year was a contentious one; it was the year that the school system had to comply with court-ordered desegregation. No one could agree on a reassignment plan and the start of school was delayed as a result.

I shared the first 60 pages of the manuscript with the woman who’d asked for my help and she let me know in no uncertain terms that she didn’t like what I’d written. She was dismayed to see her story, her words, and those of her family, in black and white.

You have to change everybody’s names, she said. You have to make it so no one knows it’s us. Why’d you make my mama sound so stupid, she asked.

Given the freedom to fictionalize the story, and because so much is unknown and lost to time, I am relieved (and quite honestly delighted) to invent filler that can connect the scenes that actually did happen.

My favorite character to date is the private investigator, Charlie Banks. A PI was hired; he tracked the girls to Florida, and he did aid in their return. Little else about him is known, however.

One of the girls recalls that he was a little on the heavy side, so I’ve given him a sweet tooth. I put him behind the wheel of what his (former) friends called a rice-burner, a Toyota Corolla.

In a Forrest Gump kind of way he interacts with the real life top cop in Savannah, Al St. Lawrence; R&B singer Bobby “Blue” Bland at a blues club outside Tallahassee; and Rob Roy Ashmore, the proprietor of Ashmore’s Drug Store, whose sign said, “We may be small, but we got it all!” (If you read between the lines here, you can glimpse the fun that I’m having.)

Finishing this manuscript qualifies as both a “loose end” and a “no regrets” issue for me. I hate that it has taken me so long to write this story, that it has taken me so many years to tie up loose ends for the woman who initially asked me to write it for her.

So I am diligently tying, trimming, and weaving threads of a story that happened 46 years ago, hoping to make whole cloth from a collection of undisputed facts, hazy memories, and falsehoods, mending holes rent by unanswered questions and unsaid truths.

(An excerpt from this project is in my short story collection, MotherLoad.)