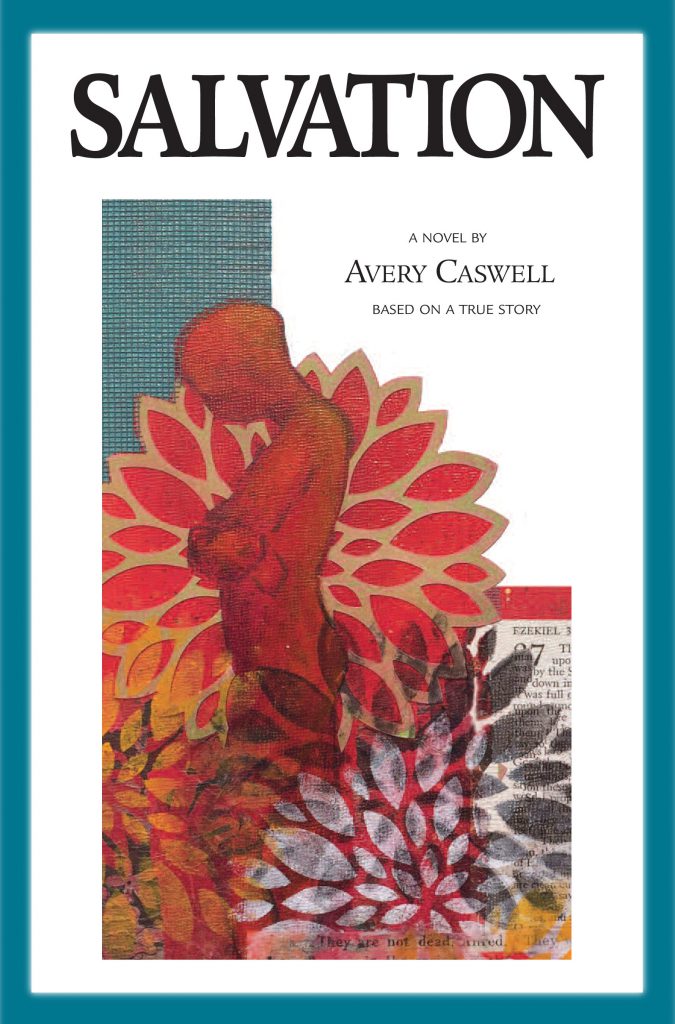

Cover Story

A few years ago, Hyong Yi had a crazy, brilliant idea for not one book, but two. He had enlisted a group of artists to illustrate 100, three-line poems, love notes he had written after he lost his wife Catherine Zanga to ovarian cancer. He was looking for a book designer and as luck would have it, Ed Williams, former editor at the Charlotte Observer, suggested he give me a call.

At the time, I had been working on a writing project for what seemed like forever. A decade before, a woman had walked up to me at daycare while we were picking up our daughters. “You’re a writer, right?” she asked.

I nodded, but it was barely the truth. I had declared my intention to write, but had nothing to show for it yet.

“I want you to tell my story,” she said. “Me and my sister were kidnapped by an evangelist in 1971. Nobody in the family talks about it so I need someone to tell it.”

An embarrassing number of years passed while I tried to do her incredible story justice. I interviewed surviving family members. I went to the library and read microfiche versions of 1971 newspapers. I hit a lot of dead ends trying to find additional information to flesh out a story based on the girls’ trek through the Deep South in 1971 in a wood-panelled station wagon with a traveling evangelist who was prone to spouting Ezekiel.

I finally had sixty pages to share and the woman hated nearly every word. “You got to change all the names,” she said. “I don’t want anyone knowing this was me.” I was forced to admit that I might never wrestle the story, even in a fictionalized version, into any semblance of a book.

Then Hyong Yi provided a welcome diversion, asking me to design his books, 100 Love Notes and the #100 Love Notes Project. Emily Andress invited me to a Ciel Gallery event where I met some of the artists involved with the project. I became excited about the design possibilities viewing works by Tina Alberni, Diane Pike, Pamela Pardue Goode, Jen Jovan, Marianne Huebner and more.

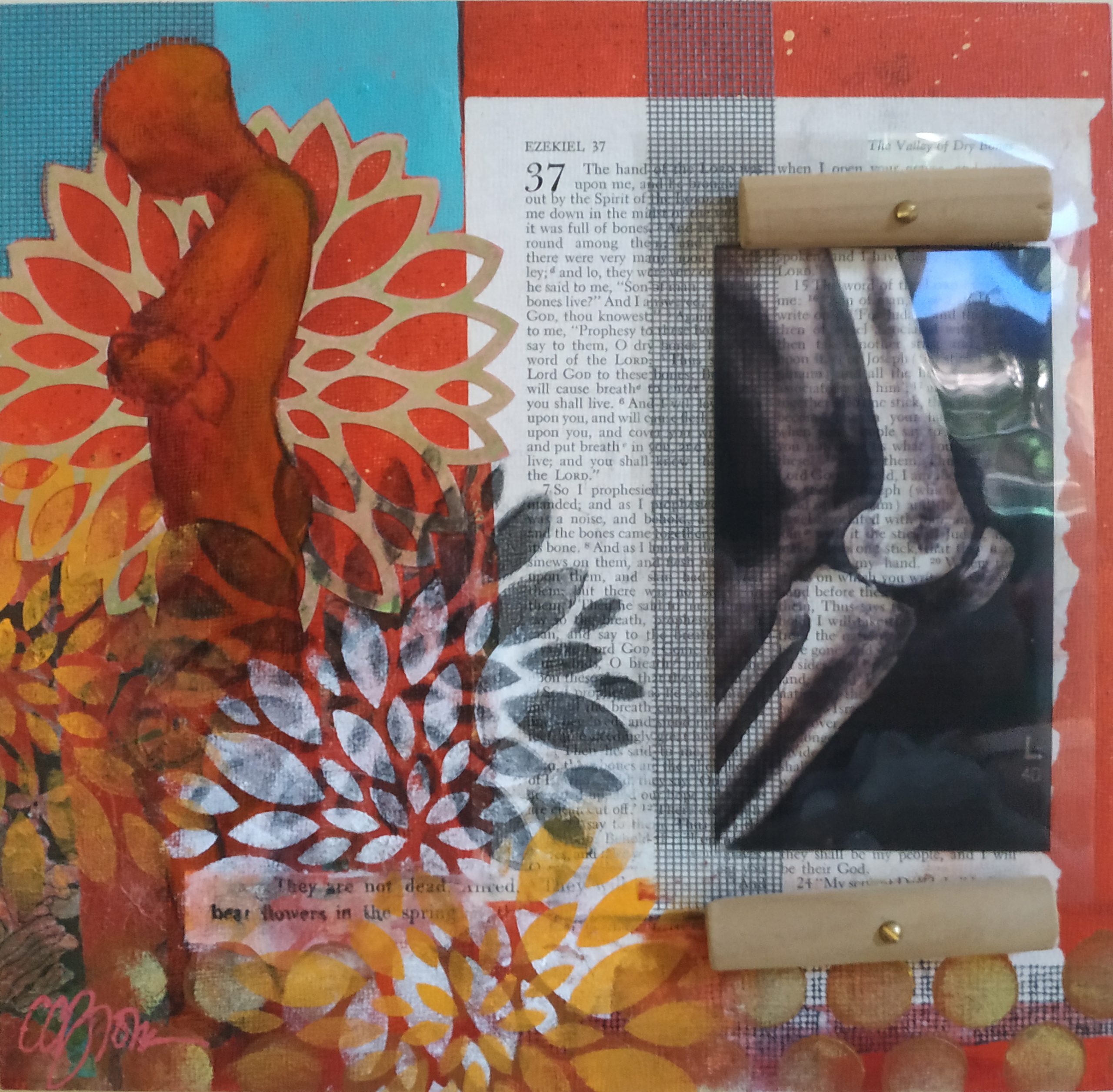

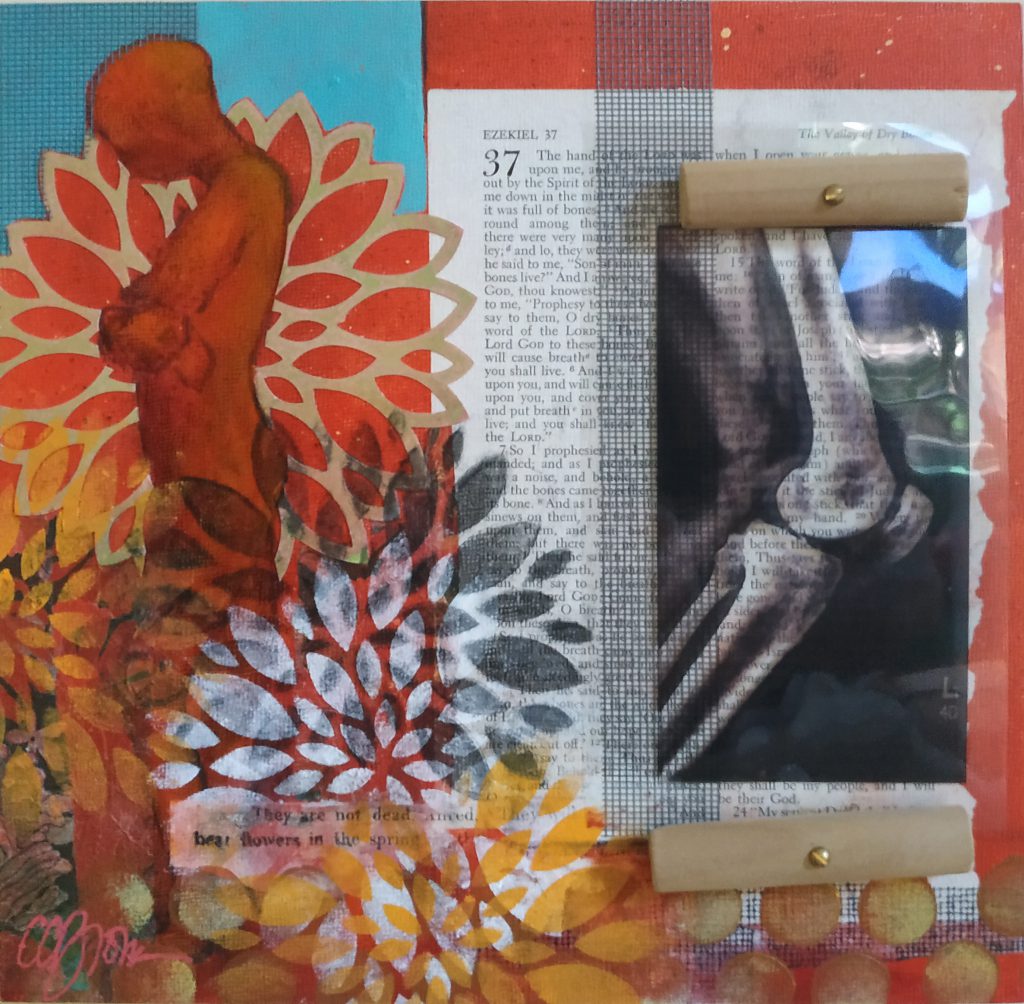

A collage by Caroline Coolidge Brown, however, stopped me in my tracks. A sad and puzzled-looking girl, rendered in orange, stood in profile; behind her a screen, around her flowers—some, stained and looking as if they’d been run over. Two pieces of wood secured a fragment of an x-ray; behind that was a Bible page, Ezekiel, Chapter 37, which begins: “The hand of the Lord was upon me.”

Well, the hand of the Lord slapped me upside the head. Right there was SALVATION. There was the window screen that kept seven-year-old Glory from being snatched by the bogey man; the wood-panelled station wagon she’d ridden in for months, an x-ray revealing inner trauma. But truly what were the odds that, of all pages from the good book, Caroline Coolidge Brown chose a page from Ezekiel?

I hung it directly across from my desk and went back to the drawing board, so to speak. The floodgates opened. Tom Hanchett at The Museum of the New South connected me with Michael Moore, himself a former resident of Druid Hills where the girls had lived. Poet Diana Pinckney, planning a trip to Savannah, was looking for someone to share the driving. In Savannah, Sharen Lee, reference librarian at Bull Street Library, pulled old city maps and city directories and more for me, revealing in great detail the place where the girls’ fraught journey began.

That fall, I was chosen to be Lenoir-Rhyne University’s Writer-In-Residence; this appointment gave me the time and space to pull everything together and finally complete SALVATION.

More trials and tribulations occurred along the path to publication, but once a contract was signed, the publisher asked, strictly as a courtesy, I’m sure, if I had any thoughts about the cover. Oh yes, indeed I did.

Tracing the many threads tied to this project, I am amazed at how many strands there are, and I am overcome with gratitude. Thank you Ed Williams, Hyong Yi, Emily Andress, Tom Hanchett, Diana Pinckney, Sharen Lee, Lenoir-Rhyne University.

And Carolyn Coolidge Brown, thank you for the art that turned the tide. Your work will now serve as an invitation for others to turn the page and learn what happened when two young girls were kidnapped by a traveling evangelist and forced to travel the back roads of the Deep South in 1971.